最常见的妇科良性肿瘤——子宫肌瘤

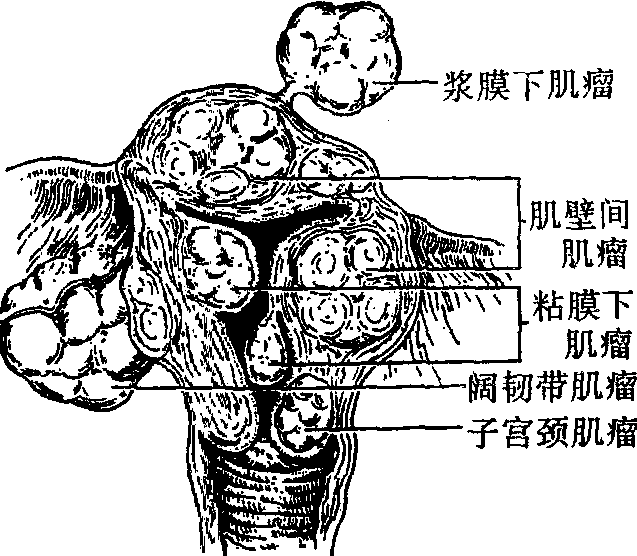

子宫肌瘤(见图7.3-4)是女性生殖器官中最多见的一种良性肿瘤,多发生于中年妇女。子宫肌瘤发生的原因,一般认为可能与长期雌激素刺激有关。肌瘤一般仅见于初潮后妇女,绝经后肌瘤多逐渐萎缩;肌瘤常并发子宫内膜增生,而后者为受雌激素过度刺激所致;妊娠时雌激素水平增高,肌瘤多迅速增大;口服或注射雌激素,可加速肌瘤生长。绝大部分肌瘤生长在子宫体部,只有1%—2%的肌瘤生长在子宫颈部。肌瘤原发于子宫肌层,子宫体部的肌瘤随着肿瘤的增大可向不同方向生长,按与子宫肌壁的关系不同而分为:

❶肌壁间肌瘤;

❷浆膜下肌瘤;

❸粘膜下肌瘤。子宫肌瘤常为多发性,常有上述二或三种肌瘤同时存在。多数子宫肌瘤无症状,仅於妇科检查时发现,肌瘤大小不一定与症状成比例,而与生长部位关系密切,如粘膜下肌瘤,可较早发生不规则阴道出血;浆膜下肌瘤可长得很大而尚无症状。肌瘤的主要症状有:子宫出血;腹部肿块;压迫症状(子宫前壁肌瘤压迫膀胱,后壁肌瘤压迫直肠);白带多;不孕(约25%—35%的肌瘤患者不孕);疼痛(浆膜下有蒂肌瘤发生扭转;妊娠时肌瘤红色变性,患者可有急性腹痛)。年轻希生育的患者,行肌瘤摘除,保留子宫;粘膜下肌瘤若已脱出于宫口外,可经阴道摘除;需行子宫切除手术的为子宫超过妊娠12周大小,已有压迫症状,月经量多引起贫血,肌瘤生长迅速疑有恶变的肌瘤。一般的子宫肌瘤可随访观察,每3—6月复查一次。

图7.3-4 各种型子宫肌瘤