细胞骨架xibao gujia

真核细胞的细胞质中一些呈纤维状的结构,与保持细胞形状和细胞运动有关。根据结构和粗细不同,可分为微管、微丝、中等纤维和微梁骨架等。微管呈中空管状结构,直径为25微米,长度不等。管壁由13条原丝平行排列围成。原丝由微管蛋白组成,微管表面尚有起稳定作用的其他蛋白质。微管在细胞中有的为单独存在,有的为成束存在,有的则构成中心粒、纺锤体、纤毛和鞭毛等细胞器。微管的主要功能与细胞运动、细胞内某些物质的定向运输、有丝分裂、植物细胞壁形成,以及保持细胞形状有关。微丝是最细的一种纤丝,多分布在近细胞核的下方。上皮细胞中的丝网和肌细胞中的肌动蛋白丝属于此类,微丝与细胞运动有关。中等纤维的粗细介于微管和微丝之间,直径为10毫微米左右。动物表皮细胞中的张力原纤维就是由中等纤维组成的束。此外,肌细胞中的结蛋白丝,成纤维细胞中的波形丝,神经细胞中的神经丝均属于此类。中等纤维在受拉力大的细胞中特别丰富,其主要功能是加固细胞骨架。微梁网架是遍布整个细胞质中的细线状物质连结成的立体网架,微梁的粗细从2~3毫微米到15毫微米,主要成分为肌动蛋白、肌球蛋白和微管蛋白等。微梁网架有多种功能,主要与维持细胞的整体结构有关。

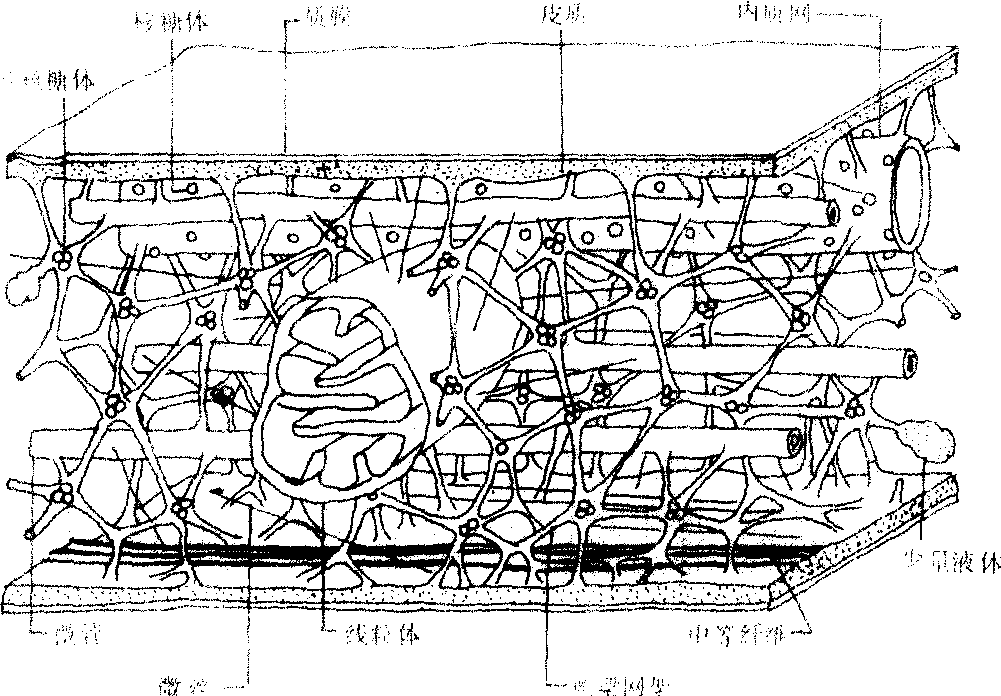

图511 细胞骨架示意图

细胞骨架

由微管、微丝、居间纤维和微梁共同构成的立体网络系统。对维持和支撑细胞,影响细胞运动等起重要作用。

细胞骨架cytoskeleton

真核细胞中一种极其复杂的网络系统。包括几类大小和化学性质不同的纤维,即微管(直径20~25 nm)、粗纤维(直径10~20 nm)、中间纤维(直径7~10nm)、微丝(直径5~6 nm)和微梁(直径3~5 nm)。它们在细胞内有特定的形态与分布,对保持细胞的形态、以及在细胞运动、细胞内运输、内吞外排、免疫行为、细胞分裂和信息传递等方面都起着重要作用。