维管束weiguanshu

维管植物(蕨类植物和种子植物)的叶和茎等器官中,由初生木质部和初生韧皮部共同构成束状结构。维管束彼此交织连接,构成初生植物体输导水分、无机盐及有机物质的一种输导系统——维管系统,并兼有支持植物体的作用。蕨类植物、单子叶植物和草本双子叶植物的茎;裸子植物与木本双子叶植物的当年幼枝;以及裸子植物、被子植物的生殖器官中,均有维管束的分布。位于叶子中的维管束,通称叶脉。在幼根中,初生木质部和初生韧皮部各自独立成束,交替排列并不连接成维管束。维管束由初生木质部和初生韧皮部所组成,根据它们排列方式的不同,可分为3种类型: 外韧维管束 (初生韧皮部位于初生木质部的外侧)、双韧维管束 (初生韧皮部在初生木质部的内外两侧)、同心维管束 (由一种维管组织包围着另一种维管组织)。裸子植物和木本双子叶植物的维管束中具维管形成层,能增生组织,称为无限维管束,蕨类植物、单子叶植物的维管束中无形成层,维管束不再继续生长,称为有限维管束。在初生的植物体中,维管束相互连接、错综复杂。茎中的维管束进入叶子里,通过茎的皮层到叶柄基部的一段维管束,即叶迹。同样,侧芽发生后,由枝迹将茎的维管束与侧枝维管束相互连接。根中的维管组织的排列与茎不同,它们之间的联系通过一个过渡区与茎的维管束相连,茎再通过叶迹和枝迹同侧枝与叶子的维管束连接,这样在初生植物体内构成一个完整的维管组织系统,主要起输导和支持作用。

维管束vascular bundle

由木质部、韧皮部或包括形成层组成的束状部分。它们错综地贯穿于维管植物的各器官中,主要功能为输导水分、无机盐类和有机养料,对植物体也有支持作用。

根据维管束内有无形成层,可将维管束分为有限维管束和无限维管束两类。有限维管束在其形成过程中,由于原形成层全部分化为初生木质部和初生韧皮部,不产生形成层,不能形成次生组织,大多数单子叶植物中的维管束属此类型。无限维管束在初生木质部和初生韧皮部之间有形成层,能分裂产生次生组织,这种维管束见于双子叶植物和裸子植物。

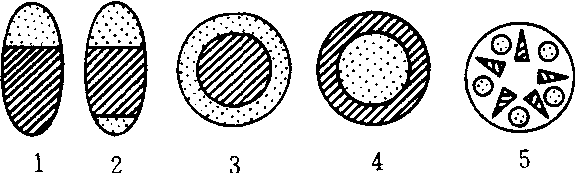

还可根据维管束中木质部和韧皮部的排列情况将维管束分为4种。❶外韧维管束: 韧皮部在外侧,木质部在内侧,一般种子植物茎、叶中的维管束属此类型;

❷双韧维管束: 木质部的内、外两侧都有韧皮部,见于葫芦科、茄科、旋花科、桃金娘科的一些植物茎中;

❸周韧维管束: 韧皮部围于木质部外围,蕨类植物的根状茎内,秋海棠、大黄等植物的茎中均存在周韧维管束;

❹周木维管束: 木质部包围于韧皮部的外围,例如胡椒科的一些植物茎中,香蒲、鸢尾、铃兰的根状茎中均为周木维管束。另外,有人曾将幼根的维管组织称为辐射维管束,但幼根的初生木质部具若干辐射角,初生韧皮部间生于辐射角之间,呈交叉排列,并不结合成维管束。

如从维管束的发生来进行分类,又可分为初生维管束和次生维管束两类。由原形成层分化而来的维管束,称为初生维管束。有些植物如蓖麻茎中的部分维管束,由束间形成层分裂产生; 龙血树、丝兰、芦荟茎在初生维管束外薄壁细胞中次生组织加厚,经过分裂和分化而形成维管束; 甜菜肥大直根由副形成层分裂活动形成许多呈同心圆排列的维管束,这些维管束统称次生维管束。

维管束

植物体内束状输导组织。由木质部、韧皮部及其间的机械组织构成。裸子植物和双子叶植物维管束中,木质部和韧皮部之间有形成层,能增生组织,称无限维管束。单子叶植物的维管束中,则无形成层,故无组织的新生,称有限维管束。

维管束vascular bundle

由木质部和韧皮部共同组成具有输导机能、兼有支持作用的束状复合结构。有的在木质部和韧皮部之间还有形成层。叶片内的叶脉、丝瓜老熟果实中的丝瓜络,以及柑橘果实内果皮上的橘络都是肉眼所见的维管束。维管束由原形成层发育而来,有的完全分化为初生木质部和初生韧皮部,这类维管束称为有限维管束(见于蕨类植物、单子叶植物)。有的原形成层除分化出初生木质部和初生韧皮部外,中间保留一层分生组织——形成层,以后由此向内产生次生木质部,向外产生次生韧皮部,这类维管束称为无限维管束(见于裸子植物、双子叶植物)。根据初生木质部与初生韧皮部排列的形式,可分为外韧维管束、双韧维管束、周韧维管束、周木维管束、辐射维管束等类型。蕨类植物、裸子植物和被子植物具有维管束,称为维管(束)植物。

维管束的类型

1.外韧维管束 2.双韧维管束 3.周韧维管束 4.周木维管束 5.辐射维管束

(图中斜线为木质部,黑点为韧皮部)