单手肩上传球Danshou jianshang chuanqiu

持球者用单手将球从肩上传出的动作, 是远距离传球的一种方式。

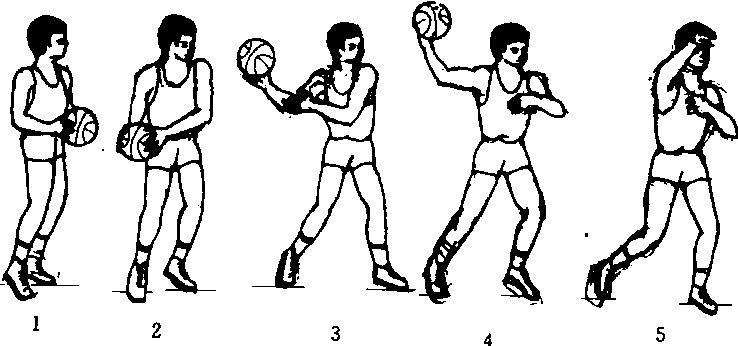

动作要领 两脚前后开立,右(左)手将球引至侧后方,身体稍向右(左)转,右(左)臂迅速前摆,利用前臂、手腕和手指的力量将球经肩上传出。传球后,身体重心随之移到右 (左) 脚上。

教学重点 ❶徒手模仿练习。体会传球的用力顺序。

❷二人单手肩上传球练习。掌握传球时的甩臂和扣腕动作。

❸抢篮板球后远距离单手肩上传球练习,培养与发动快攻战术相结合的能力。

单手肩上传球

是单手传球中一种最基本的方法。这种传球力量大,球飞行速度快,常用于中、远距离传球。特别是长传快攻多采用这种传球方法。其持球手法与双手胸前传球相同。双手持球于胸前,两脚平行开立。右手传球时,左脚向传球方向跨出半步,同时将球引至右肩侧方,右肩后转,左手扶球,右手持球后下方,手腕后屈,出球时,在右脚蹬地的同时转腰、转肩,带动右肘小臂向前摆,并向前扣腕以带动食指、中指、无名指用力拨球,将球传出。老年人练习时,先做徒手模仿练习,体会单手肩上传球的用力顺序,然后两人面对面做单手肩上传球练习,以掌握传球时的甩臂和扣腕动作。老年人练习时,在身体转动瞬间,注意用力连贯、协调,不宜过猛。