库仑扭秤kulun niucheng

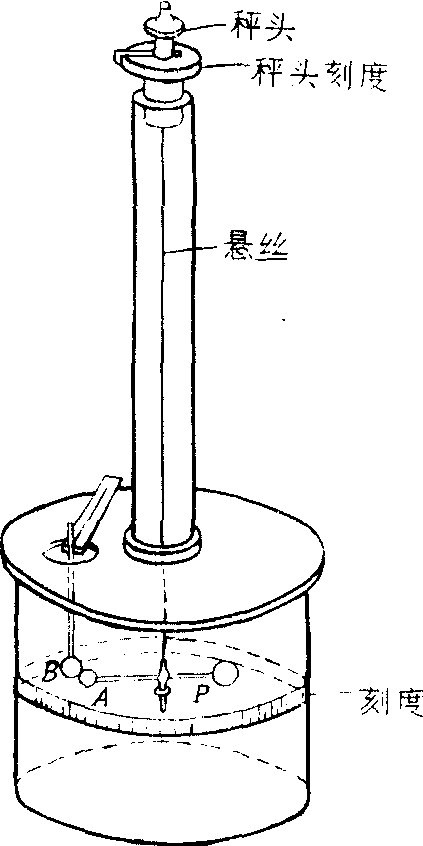

库仑设计的用以直接测定两个静止点电荷的相互作用力的实验装置。扭秤的结构如下图,悬丝与秤头固定,秤头可带动悬丝转动,其转角β可由秤头刻度读出。在悬丝下端挂一横杆,杆的一端有一小球A,另一端有一平衡物P,横杆可带悬丝绕悬丝轴转动,其转角α可由大圆筒外的刻度读出。A的旁边还有一固定小球B。令A、B带同性电荷,A因受B的斥力而转过一定角度,直至悬丝的扭力矩与A所受的静电力矩平衡为止。设此时读数为α1,相应的A、B之间的距离为γ1。由悬丝扭角可测知点电荷A、B之间的静电力。为测得静电力与距离的关系,需要在不改变A、B各自所带电量的前提下改变A、B之间的距离。为此让秤头沿相反方向扭转悬丝,使球A重新向B球靠近,例如使得A球与B球的距离γ2=γ1/2。读出此时秤头反向转过的角度β2(由秤头刻度读出)和横杆正向转过的角度α2。A、B球相距γ2时的静电力可由此时悬丝扭转的角度α2+β2而获得,即悬丝扭角ᵠ为横杆正向转角α与秤头反向转角β之和。当γ=γ1时,β1=0,ᵠ1=α1+β1=α1;当γ=γ2=γ1/2时,ᵠ2=α2+β2。库仑的原始实验数据如下表所示:

| 球A、B电量不变情 况下的两次实验 | 横杆转角α | 秤头转角β | 悬丝扭角 φ=α+β |

| 1 | 36° | 0° | 36° |

| 2 | 18° | 126° | 144° |