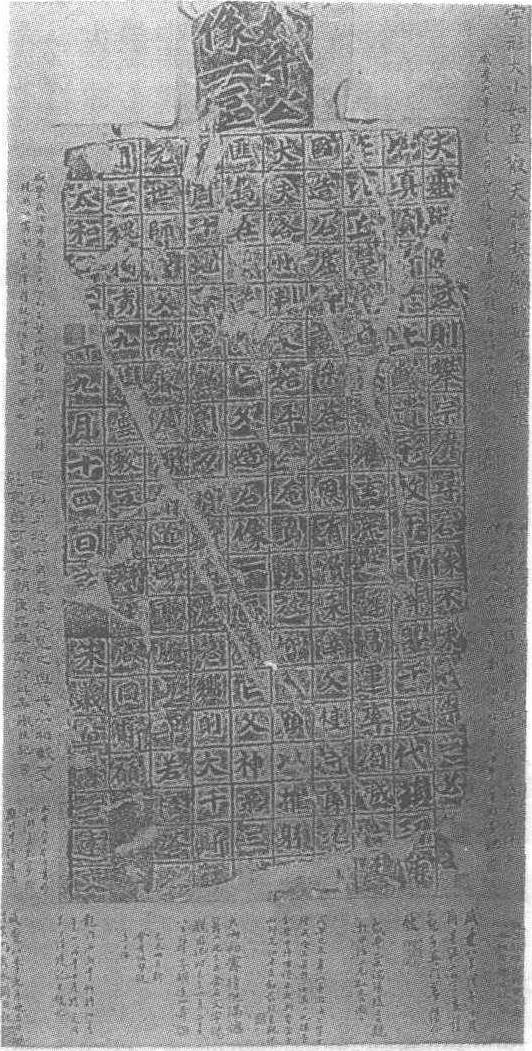

始平公造像记

北魏。太和二十二年(公元498年)九月刻,高75厘米,宽39厘米。河南省洛阳龙门山古阳洞北壁。此造像记是《龙门四品》之首,全称《比丘慧成为亡父洛州刺史始平公造像记》,简称《始平公》。由孟达文撰文,朱义意书。额阳文正书“始平公像一区”2行6字,造像记楷书10行,行20字,起笔税利,行笔方折铺毫,转折果断顿出,收笔雄强健劲,结体宽博疏阔,北朝书风表现得淋漓尽致。清胡鼻山跋云:“字形大小如星散天,体势顾盼如鱼戏水,方笔雄健允为北碑第一。”康有为《广艺舟双楫》云:“遍临诸品,终之《始平公》,极意峻宕,骨格成,形体定,得其势雄力厚,一身无靡弱之病,且学之亦易似。”北京故宫博物院和北京图书馆藏此造像记的拓本,北京文物出版社有影印本。