纤维分离fiber defibrating

用机械或化学机械方法将木材或其他植物纤维原料,分离成单体纤维或纤维束的工艺过程。要求分离后的单体纤维和纤维束具有一定的表面比和长宽比,使纤维间有良好的交织性能,在降低能耗基础上要求纤维保持固有的强度和获得较高的纤维得率。纤维质量,不仅影响纤维板生产过程的成型、热压工艺,而且也影响纤维板产品质量。纤维分离的方法大致分为机械法、化学机械法、爆破法和热磨法四大类别。中国纤维板生产的纤维分离方法,主要是采用热磨法。

机械法 将纤维原料预先用水浸泡或不经浸泡,依靠机械力的作用使之分离成单体纤维或纤维束。又称纯机械法。根据原料形态不同,机械法又可分为磨木法和木片磨木法。纤维板工业常用的是木片磨木法,又称高速磨浆法,以木片或经切碎的植物纤维茎秆为原料。原料直接或预先经热水浸泡或用饱和蒸汽加以汽蒸,而后送到磨浆机进行纤维分离。该法常见的设备有盘式磨,即圆盘磨浆机。圆盘磨浆机有单圆盘磨浆机和双圆盘磨浆机(又称高速磨浆机)。木片磨木法适应于各种原料的磨浆,纤维浆料色泽较淡而均匀,纤维的分离度较高,损伤的纤维量也比木段磨木机少。另外还有已不多见的荷兰式打浆机、锤式打浆机等。这两种方法,原料只经过初步水浸处理,虽然得率较高,但耗电量较大。

化学机械法 将原料预先经过化学药剂处理,使其内部结构,特别是木质素和半纤维素受到一定程度的软化溶解和破坏,再通过机械力作用使之纤维分离。这种方法对于处理硬阔叶树材和禾本科植物纤维类原料较为理想。化学处理常用的化学药剂有亚硫酸钠、碳酸钠、苛性钠、石灰等。处理方法有药剂浸渍法、药剂液相蒸煮法和汽相蒸煮法等。化学机械法分离纤维,不仅要消耗大量的化学药剂,而且会产生大量的废液,污染水质和环境。这种方法对木质素和半纤维素的溶解和破坏较为严重,并影响纤维得率。此外,还要考虑设备的防腐问题。防腐办法,一般将设备内衬涂防腐涂料或用不锈钢制作,也可在原料中加入适量的碱性化学药剂,以中和木材水解所产生的有机酸。在纤维板工业上已很少采用这种分离纤维的方法。

爆破法 该法是1924年由美国人马森(W.H.Mason)在里曼(Lyman)1858年专利基础上改进而成的纤维分离方法,故称为马森奈特(Masonite)法。该法是将原料放入一个高压容器中,在高温高压瞬间处理。预先在1.0~4.0兆帕蒸汽压力下处理15~40秒,再在7.0兆帕蒸汽压力下处理4~5分钟,使木质素软化和碳水化合物部分水解,然后迅速打开阀门降压,使木片爆破成棉絮状的单体纤维和纤维束。这种分离纤维的方法使木材可溶成分尤其是半纤维素大部分溶解。一般的纤维得率仅为70~80%,所解离的纤维浆料颜色呈褐色。但该法可促使纤维的可塑性增大,有利于提高纤维板产品的耐水性和尺寸稳定性。爆破法在高温高压状态下工作,对设备的维护保养及操作技术要求十分严格,这也是影响该法推广使用的重要原因之一。

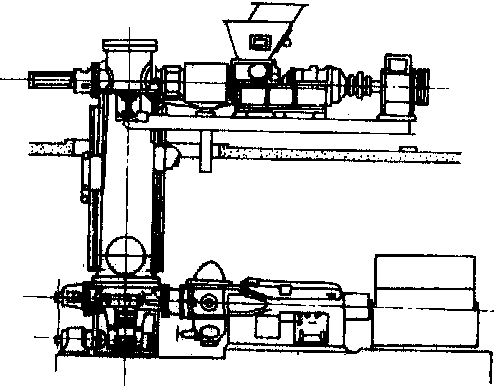

PSDR型热磨机

热磨法 又称热力机械磨浆法。该法是将原料用热水或饱和蒸汽在特定温度和压力范围上进行软化处理。所采用的机械设备因由原料软化蒸煮部分和解纤部分组成整体,故称热磨机。该机是1931年由瑞典阿斯普伦德(A.Asplund)发明。预先将原料在蒸汽压力0.6~0.8兆帕(约150~180℃)条件下处理2~5分钟,使木片胞间层的木质素软化,再通过螺旋进料装置将软化了的木片送入磨浆机磨室体内进行机械分解。这种方法特点是:使胞间层及细胞壁的木质素软化或部分溶解,不仅缩短软化时间,而且软化处理效果也较理想;动力消耗比纯木片机械磨浆法要小;所分离的纤维具有柔韧性,纤维的破坏也较少。故用此法制得的纤维浆料所压制的纤维板产品,其物理力学性能均很理想。这种分离纤维的方法在世界纤维板工业上应用十分广泛,如阿斯普伦德(Asplund)法的PSDR型热磨机(见图);BAUER法(高速磨浆法)的PDDR型热磨机;中国纤维板工业普遍采用的纤维分离机如QM型、KG型、XR型等分离纤维设备,均为该类型的热磨机。

见热磨机