数学模型方法shuxue moxing fangfa

数学模型就是根据研究目的,对所研究的过程和现象(称为现实原型或原型)的主要特征、主要关系,采用形式化的数学语言,概括地、近似地表达出来的一种结构.所谓“数学化”,指的就是构造数学模型.通过研究事物的数学模型来认识事物的方法,称为数学模型方法,简称为MM方法.

数学模型是数学抽象和概括的产物,其原型可以是具体对象及其性质、关系,也可以是数学对象及其性质、关系.

数学模型有广义和狭义两种解释.广义地说,数学概念,如数、集合、向量、方程都可称为数学模型.

狭义地说,只有反映特定问题和特定的具体事物系统的数学关系结构才被称为数学模型.一个数学模型常常又包含着若干小的数学模型.

使用数学模型方法的步骤与要求是:

❶建立数学模型.数学模型要反映现实原型的本质特征和主要关系;要加以合理的简化;要有严密的逻辑结构,以利推演和获得真实的结论;

❷对数学模型进行检验和求解.检验所建立的数学模型是否反映了对象的主要特征和关系,能否改进、简化.然后,用数学手段处理数学模型,得出数学解;

❸对数学解进行解释和评价.

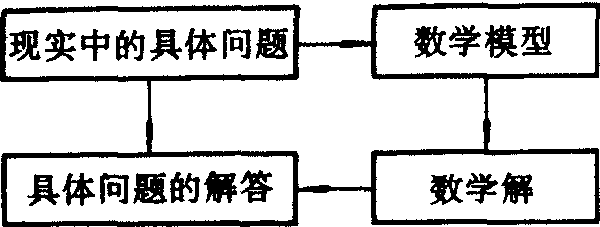

上述过程用框图可表示如下:

数学模型方法是数学科学研究和创新的重要方法之一.数学模型方法对于中学数学教学具有较深刻的影响.它要求数学教师重视揭示知识的产生和运用,让学生掌握知识的来龙去脉,使学生获得具有广泛联系的系统的结构化的知识,这样的知识是培养学生数学能力的重要基础之一.