生产力shengchanli

又称生产量。包括单位时间(通常为一年)内植物群落单位面积生产的全部有机质(干重或能量单位)总量(称总第一性生产力)和动物同化有机质的数量(称为第二性生产力)。除去动植物自身消耗的部分以后的产品即净生产力。如果总第一性生产等于呼吸作用的消耗量,则植物群落的净生产力为零,刚好能维持自身现状,总的内能没有变化。只有净第一性生产出现正值时,植物群落才能积累生物量,使生态系统得以发展。

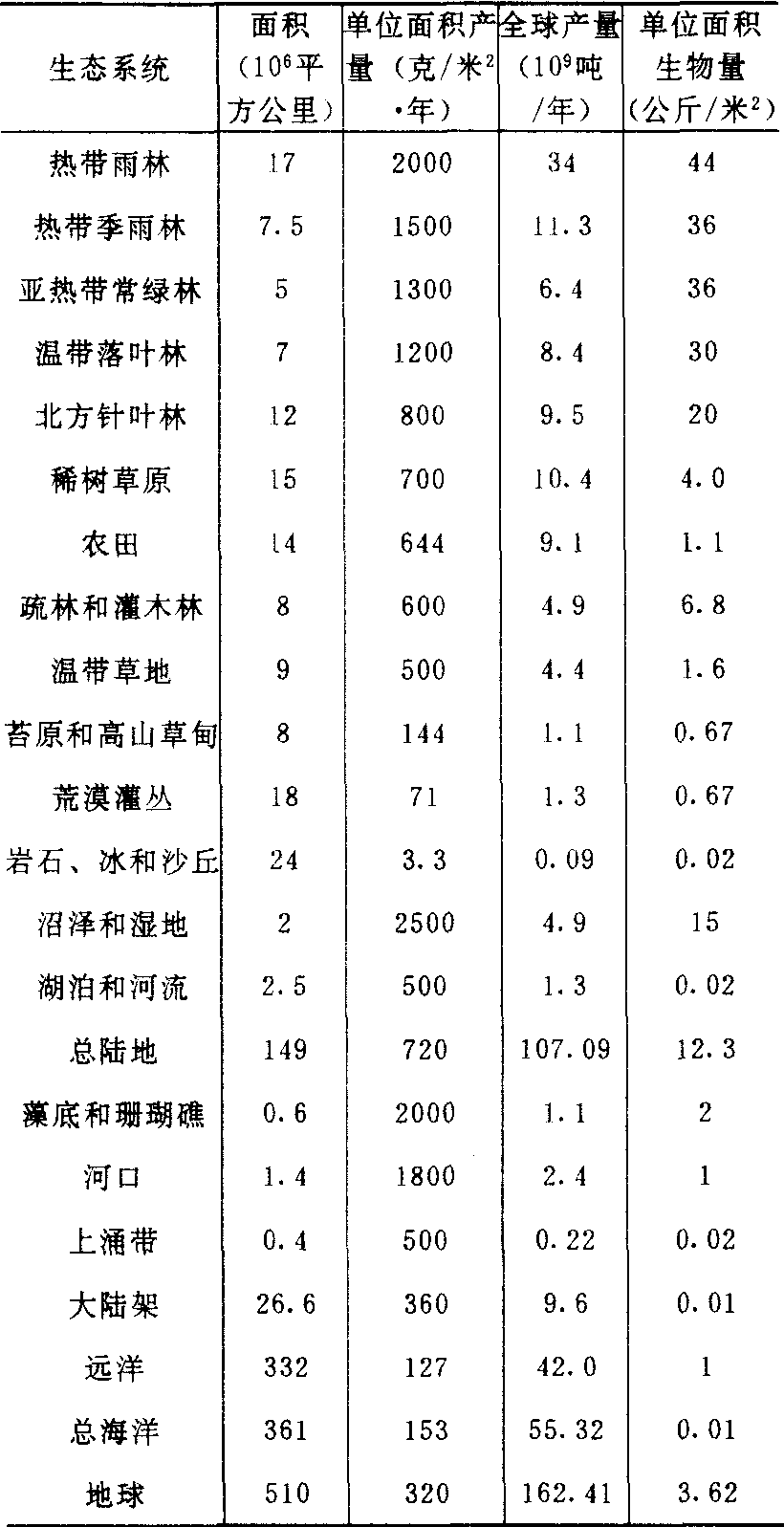

各类生态系统总第一性生产力相差悬殊,如热带农业、珊瑚礁和沼泽等生态系统的第一性生产力为40~100千卡/米2/日,荒漠和远洋则少于4千卡/米2/日。全球各类生态系统的净第一性生产和植物生物量可见下表。

生态系统的净第一性生产力,不仅在类型之间有差异,而且还随发育阶段而改变。从生态系统的幼年期开始,是不断增加的。当达到一定年龄时,由于呼吸和消耗也随之加大,净第一性生产力趋于下降。影响第一性生产力的首先是光能有效性,其次二氧化碳和含水量也是制约因素。此外温度、微量元素供给,消费者和分解者的种群波动等都会产生一定影响。

提高系统的净初级生产力主要是增加可利用部分的比例。在农业上,通过改良作物品种,提高谷粒和茎杆比来实现;在牧业上,改良草场,增加优良牧草的比例,就可以提高净初级生产力。

地球生态系统的净第一性产量表

(引自曲仲湘等的《植物生态学》,1982)

生产力shengchanli

生产力是人们征服自然、改造自然以获取物质生活资料的能力。生产力作为解决社会同自然的矛盾的物质力量,主要是由劳动者、劳动资料、劳动对象三个要素所构成。劳动者是指具有一定生产经验和劳动技能,并运用劳动资料实现物质生活资料生产的人,它包括生产过程中的劳动者和直接为生产过程服务的脑力劳动者。劳动者是生产活动的发动者和组织者,是生产力诸要素中起主导作用的要素。劳动资料是指人们在劳动过程中用以改变或影响劳动对象的物质资料,它是人和劳动对象之间的媒介物。生产工具是劳动资料的主要方面,它是人类劳动器官的延长,是人的体力和智力的物化,又是衡量生产力发展水平的客观尺度。劳动对象是指人们通过劳动过程对之进行加工,使之具有使用价值以满足人类社会需要的物质资料。生产力三要素有机结合,构成现实的生产力。此外,科学技术也是决定生产力发展水平的一个重要因素。虽然科学技术不是生产力中的实体性要素,但是它可以转化为劳动者的劳动技能和工艺操作方法,科学技术上的发明创造可以引起劳动资料和劳动对象的变革和进步,从而引起生产力的发展。所以,“劳动生产力是随着科学和技术的不断进步而不断发展的。”(马克思:《资本论》第1卷,第664页)

生产力

生态系统生态学用语。生态系统的生物生产的全过程中,单位时间制造有机物的总量。有时还注明单位面积。分总初始生产力、净初始生产力、净群体生产力和次级生产力等。

生产力

见“哲学”中的“生产力”。

生产力

又称“社会生产力”。人们征服、改造自然的能力。是客观的物质力量;反映人与自然的关系。包括三个要素:具有一定生产经验和技能的劳动者;以生产工具为主的劳动资料;劳动对象。劳动者是其首要的能动的因素。生产工具是其发展水平的物质标志。它是生产方式中最活跃、最革命的因素,决定着生产关系的性质和发展;是社会发展的根本动力。参见“生产方式”。

生产力

亦称“社会生产力”。人们改造和变革自然界表现出来的能力。其构成的物质要素包括: (1)具有一定的科学技术知识、生产经验和劳动技能的劳动者; (2)包含着一定的科学技术因素、以生产工具为主要标志的劳动资料; (3)劳动对象,即被加工改造的自然物或已加工过的原材料等(有人把劳动资料和劳动对象合称为“劳动资料”)。生产力表示人和自然的关系,亦即是人类改造变革自然界过程中表现出来的能力。在生产力构成的各种物质要素中,它们在实际生产过程中都是不可缺少的,但各自起的作用不同。劳动者是能动的、积极的要素,是首要的、占主导地位的方面,因为生产工具等劳动资料,是劳动者创造出来的,物化了的知识力量; 劳动对象也只是在劳动者运用一定的生产工具作用于它们才被改造和变革的。生产工具则是生产力发展水平和划分一定经济时代的物质标志,因为生产工具的状况如何表示着人类改造和变革自然的能力如何以及人们的社会物质经济生活如何。科学技术也是生产力,但不是作为一种独立的物质要素,而是渗透到生产力的各种物质要素中。马克思说: 生产力里面也包括科学在内。科学技术是推动生产力发展的有力杠杆,并随着人类改造自然、社会生产的发展起着愈来愈重要的作用。生产力的诸物质要素彼此分离的条件下,都只能是一种可能的生产力,它们只有以一定的社会关系形式即生产关系形式互相结合才能成为现实的实际生产力,实际的社会生产过程。因此,每一社会的物质资料生产方式都是一定的生产力和生产关系的统一体。在社会物质生产中,生产力是最活跃、最革命的力量,也是社会发展的最终动力。它是一种客观物质力量并按自身的一定规律发展的,每一代人们只能在既得的、前代人创造的生产力基础上进行生产,人们不能任意选择和改变。