绒球

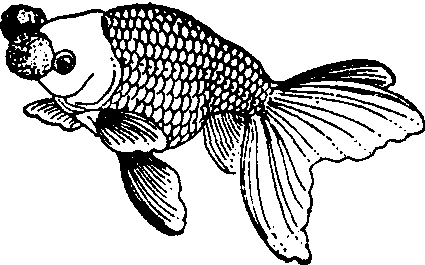

又叫“绣球”,为蛋种金鱼的代表之一。我国于1900年培育出的新品种。头狭长形,眼小;无背鳍,背部光滑,微有弓起,尾鳍短小,仅有身长的1/3,展开时有3个分叉,游泳时,平展水面;最显著特点是,2个外鼻孔间的2个鼻隔(鼻孔膜)特别发达,似1束肉质叶附着在吻的顶端,2束肉质叶团簇在一起,呈小绒球状飘动在头前,其颜色与体色基本相同。品种较多,体色各异,如蓝绒球、红绒球、紫绒球、白绒球、五花绒球和红白花绒球等。

绒球

| 词条 | 绒球 |

| 类别 | 中文百科知识 |

| 释义 | 绒球又叫“绣球”,为蛋种金鱼的代表之一。我国于1900年培育出的新品种。头狭长形,眼小;无背鳍,背部光滑,微有弓起,尾鳍短小,仅有身长的1/3,展开时有3个分叉,游泳时,平展水面;最显著特点是,2个外鼻孔间的2个鼻隔(鼻孔膜)特别发达,似1束肉质叶附着在吻的顶端,2束肉质叶团簇在一起,呈小绒球状飘动在头前,其颜色与体色基本相同。品种较多,体色各异,如蓝绒球、红绒球、紫绒球、白绒球、五花绒球和红白花绒球等。

绒球 |

| 随便看 |

开放百科全书收录579518条英语、德语、日语等多语种百科知识,基本涵盖了大多数领域的百科知识,是一部内容自由、开放的电子版国际百科全书。