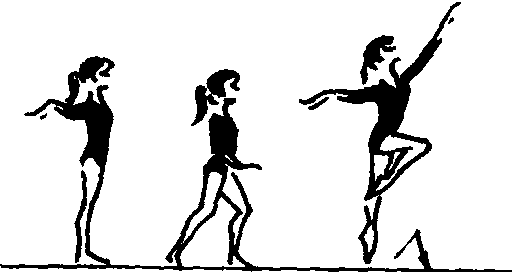

吸腿跳Xituitiao

基本舞步之一。踏跳后摆动腿屈膝前吸的跳步。

动作要领 向前一步后用力蹬地跳起,摆动腿主动吸腿,使脚掌内侧靠膝部,一臂摆至前上举,另一臂摆至后下举。同时收腹立腰,抬头挺胸,要求腾空高、舞姿充分、舒展。

教学重点 原地练习吸腿舞姿,然后跳起吸腿,最后加手臂完整练习。

| 词条 | 吸腿跳 |

| 类别 | 中文百科知识 |

| 释义 | 吸腿跳Xituitiao基本舞步之一。踏跳后摆动腿屈膝前吸的跳步。

动作要领 向前一步后用力蹬地跳起,摆动腿主动吸腿,使脚掌内侧靠膝部,一臂摆至前上举,另一臂摆至后下举。同时收腹立腰,抬头挺胸,要求腾空高、舞姿充分、舒展。 教学重点 原地练习吸腿舞姿,然后跳起吸腿,最后加手臂完整练习。 |

| 随便看 |

开放百科全书收录579518条英语、德语、日语等多语种百科知识,基本涵盖了大多数领域的百科知识,是一部内容自由、开放的电子版国际百科全书。