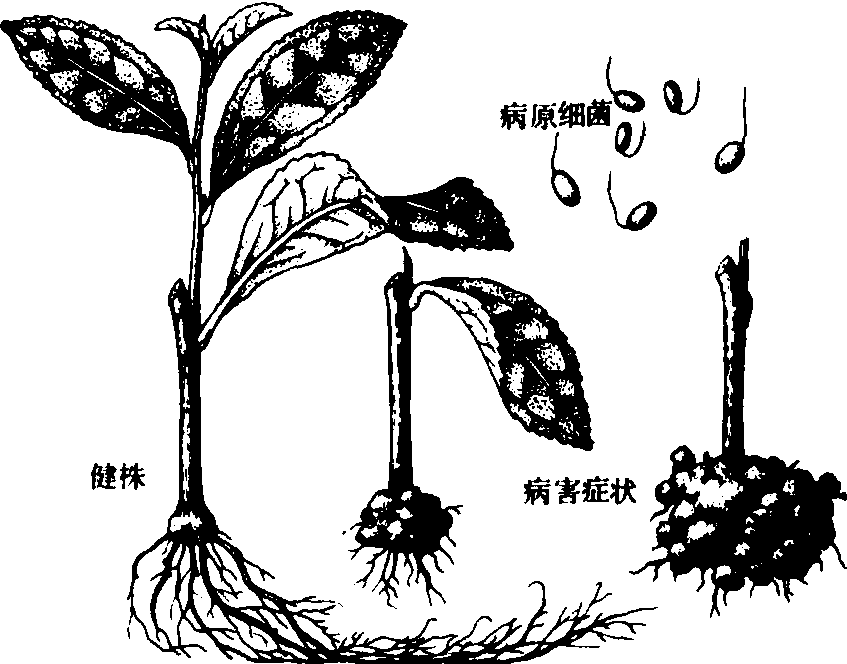

茶苗根头癌肿病tea seedling crowngall

茶树扦插苗根部的细菌性病害之一。中国各主要产茶省均有发生,日本也有记载。除为害茶外,还可为害苹果、梨、李、梅、杏等植物。

症状 扦插苗的根头切口部, 产生大小不同的癌瘤, 许多瘤团聚一堆而成大瘤, 癌瘤形状,多为球形或扁球形, 病株根系发育不良, 地上部生长衰弱,黄化矮小, 以至死亡。

病原 学名为Agrobacterium tumefaciens Smith,属野杆菌属细菌, 杆状, 长宽为1.2~5.0×0.6~1.0微米, 有1~3根鞭毛, 单极生, 格兰氏阴性,有荚膜,无芽孢, 发育适温25~30℃,最适酸碱度为pH7.3,耐酸耐碱范围为pH5.7~9.2,致死温度为51℃,10分钟。

茶苗根头癌肿病

侵染规律 带菌土壤是病害的主要来源, 病苗由伤口或切口侵入皮层组织, 侵入后, 不断刺激寄主细胞增生膨大以至形成癌瘤。因此, 伤口与切口的存在是发病的重要条件。土壤潮湿、粘重的苗圃, 以及有病苗圃地连栽最易发病。

防治 选择土质疏松、排水良好的无病地育苗,防止有病苗圃连作, 并作好地下害虫防治工作; 发现病苗, 应尽早清除。

茶苗根头癌肿病tea seedling grown gall

茶树根部病害。中国各茶区均有发生。日本也有记载。为害茶树、梨、苹果、李等多种木本植物。以扦插苗发生最为普遍。在扦插苗根部切口处形成大小不一的癌肿,多为球形或半球形,表面不光滑。病株根系发育不良,地上部生长衰弱。病原菌格兰氏阳性菌Agrobacterium tumefaciens Smith,属野杆菌属。有1~3根鞭毛,大小1.0~5.0 μm×0.6~1.0 μm。带菌土是病害的主要来源,病菌由伤口侵入,刺激寄主细胞增生,形成癌肿。黏重、排水不良的土壤易于发病。宜选择土质疏松、排水良好的无病地育苗;避免连作;发现病苗及时清除。